One day we will have left images and information that will allow people in the future to see where we are today and why they are who they are, in whatever future we have created for them. So, the photograph becomes part of cultural history in the making

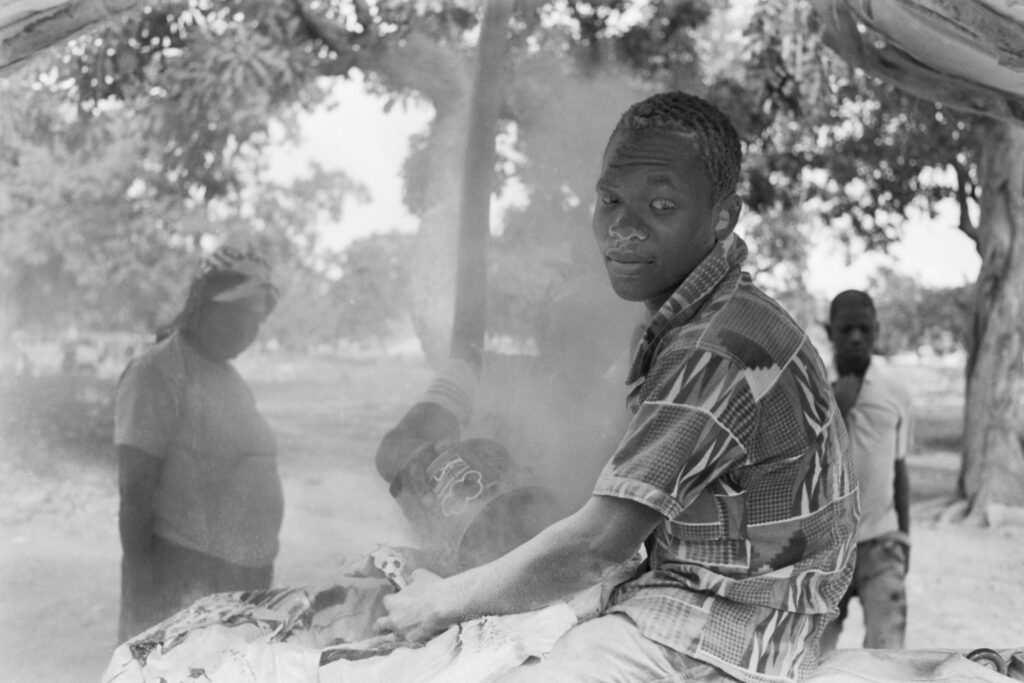

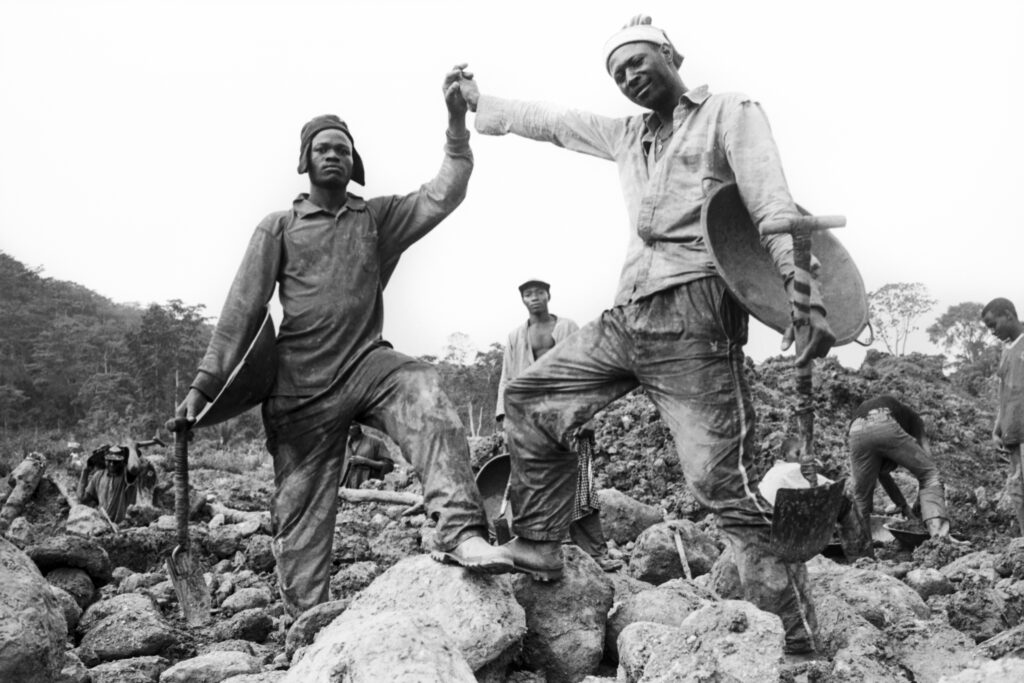

Nii Obodai works with photography, audio and text, and has a particular interest in recording and celebrating the unseen and every day in Africa. Working in black and white, his photography encompasses portraiture and ethereal landscapes. In conversation with Eleanor Fisher at the Nordic Africa Institute, he reflects on how he was drawn to portray the lives of gold miners for his series “Big Dreams, Life Built on Gold”, which is featured in an on-line exhibition: https://www.exhibitiongoldmatters.com/

EF: I know from having watched you take photos in Ghana that you have a certain way of working, can I start by asking you to describe your approach?

NiiO: My approach has been the same for the last 25 years – I am still shooting film. I enjoy the aesthetics and the process; I enjoy experimenting with film material and the chemicals, and with different printing materials. It is important that each story has its own feel, in terms of discovering an aesthetic that becomes unique to that body of work. That is where the experimentation comes in; I find working with film very satisfying.

I started with small format photography cameras and film, now most of the work I shoot is with large format film cameras. This is a more slower and engaging experience, it is more gratifying in terms of getting the kind of information that I want, especially out of landscapes, and portraiture. I get a lot more detail in large format film.

EF: I know you prefer to use black and white for the images you produce, is there a reason for this?

NiiO: Well it’s just a matter of practicality, the chemical formulas I either make myself or I can find them in my area or import them. Most of the film I have to import, but also I can use household products to make the processing chemicals and the fixers. Colour photography, it is always incredibly complicated maintaining the temperatures, like where I am here today in northern Ghana; it is incredibly hot and dry. I would need a ton of ice to develop film here. I have a lot more control with black and white processes and anyway I simply enjoy making photographs in black and white.

EF: For your series Big Dreams: Life Built on Gold. Can you explain a little about the motivation?

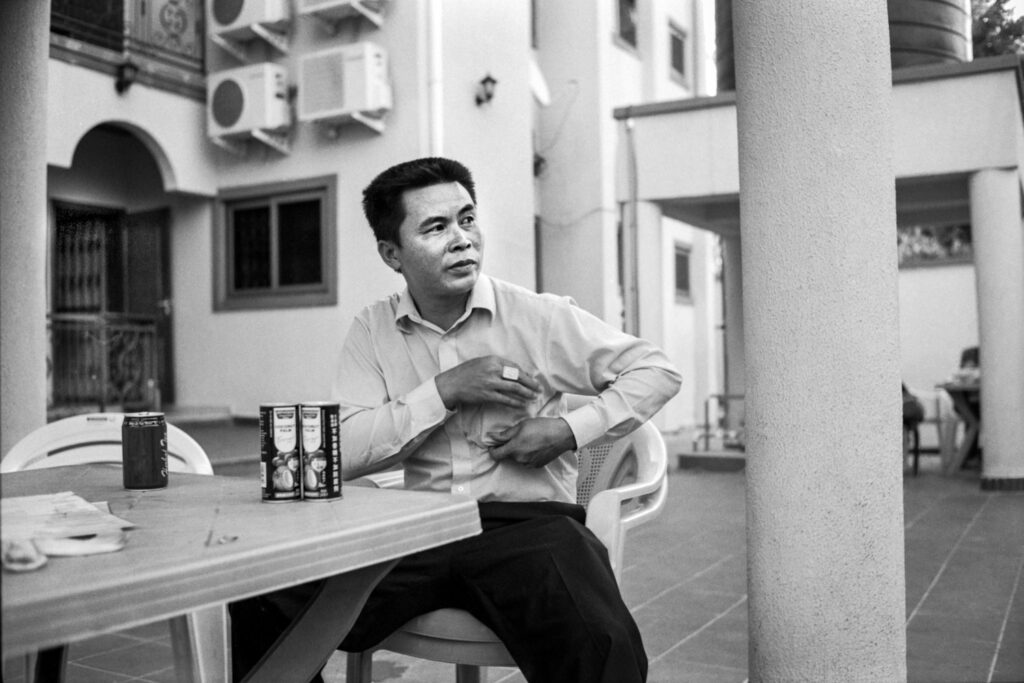

NiiO: If we go back to 2013 or 2014, I started hearing about Chinese miners in Ghana, illegal migrants coming in and acquiring concessions and digging up forest regions and basically taking over the galamsey [small-scale] mining industry. Conflict started taking place between the Chinese and local miners, I wanted to understand what was going on. There were lots of reports [in the Ghanaian media] concerning the environmental impact, the negative impact it was having on the forest and on communities, A few years before, I made a commitment to myself that I would focus the majority of my work on the environment. This story of the miners and their relationship with the environment, I really felt I had no choice. It was compelling, I had to see for myself what was happening.

At first, I thought it was all about the Chinese, because a lot of the information I was getting was coming from the radio stations and it was very graphic, about the Chinese being in conflict with local people and the devastation they caused, so there was a lot of blame on them. Then I started asking myself questions, ‘well how did they get there’ they can’t get access to land unless a Ghanaian gives them the access to the land. It’s not possible for anybody to come into Ghana and just appropriate land, it doesn’t work like that, our traditional and governing systems don’t allow for that to happen because the ownership of the land is with the people. That meant that we have to ask ourselves the question of why this is taking place?

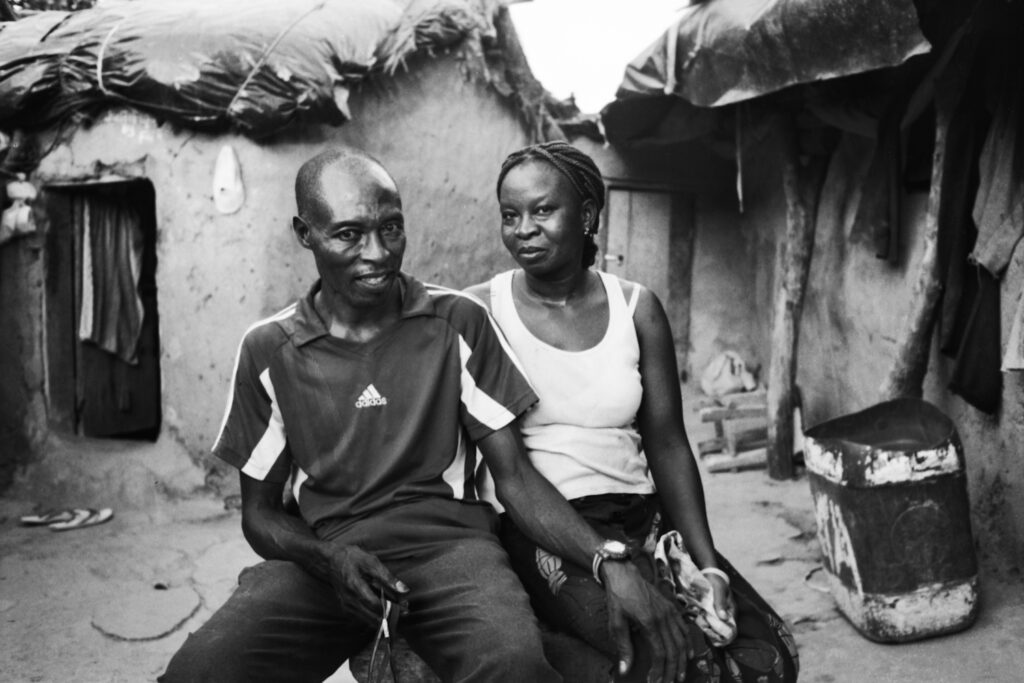

One of the fundamental ways I approach photography is from the point of view of offering whomever I am working with – whoever gives me access into their lives – dignity, and this plays a major part in our relationship building. So even with the Chinese it was not pointing blame at them or shooting them in ways that put them in compromising positions with my photography, but rather see them in a non-judgemental way, so it was really about getting to know why they had come here and what all of this means.

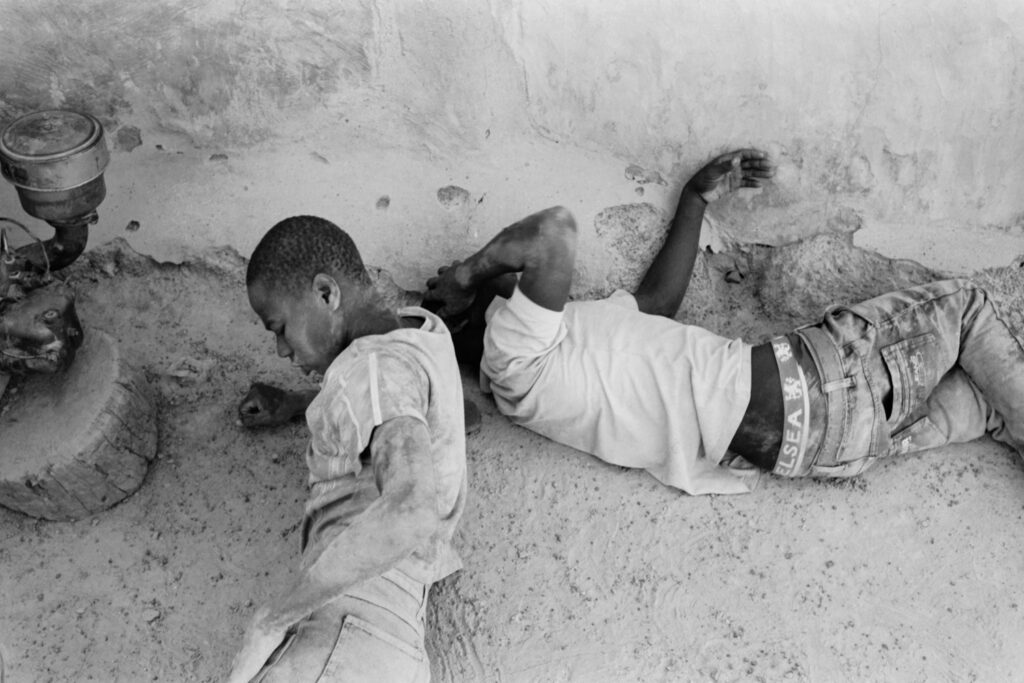

Photography is such a powerful medium to work with. Making photographs of people is a privilege, it is not something that I take as a weapon to degrade people through images. This is especially true as I come from a culture where through our history – if you look at the early history of photography in Africa – the camera was used to dehumanise people, it was used as a way to further policies and motivations for exploitation of Africa. So, photography has a history in Africa that sometimes makes us uncomfortable and we (photographers) need to be aware of that and especially those of us coming from here ourselves. When we are working, I think it is very important that we use photography in ways that actually benefit everybody and not just the image-maker or for other nefarious reasons let’s say.

So yeah, with the Chinese it was on the basis that we would engage as people meeting each other and listening to each other’s stories. As those relationships grew, it also allowed me time to start making relationships with Ghanaian miners who were taking over Chinese fields because the Chinese were being deported from the country. I started learning more about our cultural attitudes towards the galamsey. You know gold mining has been going on in this region for centuries; it is nothing new so it is important to understand the history of gold mining here, through traditional storytelling, even from spiritual aspects of gold mining. This really means getting to know people, getting to know their communities, the hierarchical systems in communities, and not just going in as a photographer and bang, bang, bang with lots of images, they look great, but……

EF: That raises an interesting question because from working in artisanal gold mining communities myself I know how much distrust there can be to outsiders. You have some very intimate portraits and I was wondering how do you build that rapport?

NiiO: Hmm – its time. Time and lots of visits. When I first approach people, they think I am working for the press or working for the government and I am not working for either so I let them know that I am coming to them more as an artist / documentary photographer. These investigations are part of my artistic practice, and the work is not there to be in any way, let us say, profit-making through the media, in terms of exposing who they are. For me the work is more than trying to explain to people today, it is actually for the generations that are not yet born, that one day we would have left images and information that would allow them to see where we are today and why, and why they are who they are in the future. It’s more about seeing the photograph as part of our cultural history in the making.

EF: I love that reflection about photography and its value for people who are not yet born, which brings me to the theme of sustainability and future generations and I think my final question. You are working with us [the Gold Matter’s project] within a transdisciplinary team, which brings all sorts of researchers together, what is your observation about what photography brings to our work and to the Team?

NiiO: When we look at our collection of works there is some really brilliant image making that has been done, especially because with the researchers you can see they are invested in their research and the people they work with. For me, you asked me the question of how do I build trust? Well, one of the things I read in most of the images, indeed pretty much for everybody in the research team is that they have worked on building trust, coming back and building upon the relationships in the locations that they are working. This has allowed us to make images beyond just the factual, that you can actually read through the photography that some good connections have been taking place in the research field, it is not just us researching them, but it is collaborative. I mean we’ve got our miners shooting film and making videos of their lives as part of the project, it’s a very intimate process that we bring into this research, its not cold.

EF: I think that is a nice note to end on, around the fact that it is a collaborative process, we could go on talking but let us leave it there for today, thank you very much Nii and I hope your trip continues to go well.

Gold Matters: Sustainability Transformations in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining: A Multi-Actor and Trans-Regional Perspective is a transdisciplinary research project, which aims to consider whether and how a transformative approach towards sustainability can arise in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining (ASGM). For more information, see www.gold-matters.org.