For artisanal gold miners in south-western Burkina Faso, the Covid-19 pandemic is creating hunger, uncertainty and disruption, including for the Tãngpogse, the female economic entrepreneurs of the gold panning sites. Compounding an already difficult context related to Jihadist terrorism, gold panning has been impeded by the closure of air and land borders, the quarantining of towns, and the establishment of curfews due to the “corona-djadist”.

For two thousand years, artisanal gold mining has been at the heart of the dynamics of West African societies. In the last decades this mining has grown in importance as a source of livelihood. As such, in Burkina Faso, gold panning has become part of an “economy of dreams” (Pijpers 2017) based on the hope of acquiring significant wealth in a short period of time, as miners’ dream of a bright future. Such dreams of a rich life, providing opportunities to improve one’s economic and social position, are in keeping with artisanal mining being a poverty driven activity.

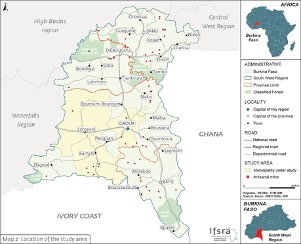

In the southwestern region of Burkina Faso, in Lobi country, artisanal gold mining involves alluvial and eluvial deposits that are close to the earth’s surface and easy to exploit. In the 2000s, this attracted a massive influx of gold panner migrants (men and women) from neighboring countries (Ivory Coast, Mali, Ghana, Niger, Togo, etc.) and other regions of Burkina Faso. This mobility of gold panners generated “borders” and “hinterlands” (Grätz 2004) creating spaces for the transaction of minerals and consumer goods in which a mode of livelihood has grown up. Against this background of multi-ethnic mobility for gold panning, the question arises what happens to this profitable economic activity with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic?

COVID-19 and gold panning

The first cases of coronavirus in Burkina Faso were reported on the 9 March 2020, with by 22 May 814 confirmed cases. When faced with the threat of a growing crisis, government drew up a response plan and set up a national response committee. Measures were introduced to reduce the risk of the pandemic spreading: the quarantine of cities with confirmed cases and of affected persons and their contacts; the closure of borders, markets, educational establishments, restaurants, bars and places of worship; the stopping of public and inter-urban transport; the introduction of a country-wide curfew; and, the prohibition of gatherings of more than fifty people. Awareness was also raised of barrier measures: hand washing, mask wearing, social distancing, coughing in a handkerchief.

To know how Covid-19 is affecting their activities, I called gold panners who I have been conducting doctoral research with in south-western Burkina Faso on the 13th and 14th of April 2020. Speaking to me, they referred to the disease as “Corona-varice”, “Corona-djadist” or “Colonel-viris”, as they sought to convey the dangerousness of the pandemic and how it is threatening their mining activities and livelihoods.

Balance for weighing of gold; gold nuggets and gold lingo

© Alizèta Ouédraogo

The gold panners I spoke to described how the Covid-19 has influenced the selling price of their gold. A gram used to be sold for 40,000 FCFA (around 61 €), but they said it currently sells for 15,000 FCFA (around 23 €). For Ouedraogo (April 2020), gold prices in Burkina have risen to 79% of the world spot price, from a low of 55% just after the COVID-19 crisis hit in March. Pre-crisis, miners were receiving 94% of the spot price. According to Zongo and Sawadogo (May 2020), the fall in the price of gold at gold panning sites in Burkina Faso was a response to the uncertainty of the global health situation, because most people believed their economic activities would be halted through control on economic activity, confinement and lack of access to gold buyers in large cities and internationally. Of course, there has also been disruption of artisanal gold supply chains internationally.

Locally miners are aware that the price of gold has not fallen on a world scale and rationalize the reason to be linked to the closure of land and air borders. “At the rate things are going, we risk our activities to be stopped, and don’t be surprised if gold diggers come to rob you at home from Ouagadougou for their survival … because they will have no other choice. The number of robberies will increase.” (Bantara site manager, telephone interview, 13/04/2020). These words highlight the hardship that gold panners are experiencing, and the lack of opportunities they envision having any time soon. According to media accounts, including by Burkina Faso’s national television reporting on the Bantara site in the southwest, gold panning activities are at a standstill. This has led to the price of gold falling at the sites (see here and here).

When I contacted the president of a gold buying and selling society (owner of gold panning sites and cyanidation ponds) by phone on the 13th of April 2020, he told me that panners don’t have any money because their (middle-man) partners and also big gold buyers (for a refinery) are abroad and not travelling to the country to buy gold. In addition to terrorism, which has led some African and foreign policymakers to limit and cap transactions and transfers by banks and the Western Union company to Burkina Faso, Covid-19 has been added as a reason to the control list. This lack of cash to buy food and survive creates severe difficulties for panners and those involved in gold supply chains locally.

Nevertheless – and despite media accounts to the contrary – gold panning continues. The amalgamation of gold using cyanide, known as cyanidation, is generally carried out in the bush in areas far from the cities; it is usually hidden and difficult to access by ordinary citizens. Therefore, security guards who do not have the financial and logistical means to enforce curfews allow cyanidation practitioners to continue as usual. In addition, the fact that gold can no longer be purchased in fact benefits certain local buyers, who obtain it at a lower price. “The activities continue, but gold does not buy more. Sometimes we have to pawn our gold as a guarantee or a pledge to our big buyers in order to get money. This money allows us to ensure a minimum of our activities and to take care of our families while waiting for the pandemic to be eradicated” (site manager). This is despite the fact that the price of gold has become very low: “nobody buys gold anymore, even for free …. It’s really corona-djadist. We cried because of djadism [jihadism]. We haven’t finished crying over our dead yet and now worse than Djadism has come” (site manager).

As for mining activities, the miners I spoke to explained they are functioning at a slower pace. They described how containment, social distancing and curfews severely limit their extraction activities. “With social distancing, the majority of gold miners are confined to houses. They’re like rats. [chuckles]. Also in the evening, the police beat people in the gallery areas to enforce the curfew. So it’s very difficult.” (site manager). It is normal for digging activities to be carried out throughout both day and night, but measures to control the spread of Covid-19 – including heavy raids by national security guards – have led to an increase in digging activities at night.

The Tãngpogse: the female economic entrepreneurs of gold panning sites

Women too are at the center of this “Corona-djadist”, being as much affected in their working lives as men and in many cases even harder hit. The majority of the gold processing ‘hangars’ are held by migrant women from neighbouring countries and other regions of Burkina Faso. Hangars are significant economic enterprises and attest to a degree of economic emancipation for women. These female entrepreneurs are called Tãngpogse, in Mooré, literally “women of the hill” (from tãng, the hill and pogse, women; in sing. Tãngpoaka). Amongst their clients are gold panners, female mineral collectors, buyers of minerals from the diggers, and the owners of the hangars themselves (Ouédraogo, Master 2 defended in 2014 and current doctoral thesis, in process).

The Tãngpogse, especially the owners of hangars, are finding it difficult to get customers for the processing of ore and are have difficulty surviving: “as the men do not get enough ore and because of the coronavirus, women are mostly confined to the sites” (woman owner of a gold processing hangar,14th of April, 2020).

Gold panners responses to the Corona-djadist

The gold panners have developed forms of solidarity to cope with this “Corona-djadist”, with mutual aid becoming more developed. Donations are also given by leaders and the gold panners’ unions. According to Zongo and Sawadogo (May 2020), the President of the Burkinabe Union of Artisanal and Traditional Goldpanners (SYNORARTRAB), South-West section, gave donations of various kinds on 21 April 2020 at the artisanal gold site of Djikando in Gaoua. As for the sites in the country that have not benefited from these donations, the gold panners have bought themselves soap and hydro-alcoholic hand washing gel.

Nevertheless, despite these forms of mutuality, the Covid-19 has called into question the spirit of sharing food, drinks and cigarettes, all normally acts goldpanners use to support one another. “Now it’s everyone at home…The measure of distancing distancing made it obvious to the gold washers not to eat from the same dish, nor to smoke the cigarette stick or drink from the same container. If a cure is not found as soon as possible, it is not the coronavirus that will kill us, but hunger” (site manager, 14 April 2020). Clearly the Covid-19 pandemic has already had a very negative impact on the lives of the gold panners (men and women) and their minimal economic functioning is causing a food crisis.

The Burkinabe government in its measures put in place to control the spread of Covid-19 must take into account gold panning, given its significance as a form of livelihood in Burkina Faso. According to the gold panners I interviewed, they are being marginalized and gold panning is being “abandoned” to its own fate. Support in terms of food and materials (soap, hydroalcoholic gel, etc.) would enable the gold panners to cope with the pandemic and the food crisis. Also, the Burkina Faso Ministry of Mines, in particular its National Agency for the Supervision of Artisanal and Semi-mechanized Mining (ANEEMAS) would benefit from conducting a discussion with the unions and gold panners’ leaders on how to sustain activities on the sites while complying with barrier measures for COVID-19. In addition to reducing the risk of contagion, facilitating this form of livelihood to continue would also help prevent gold panners, both men and women, from falling into large-scale banditry (robbery, highway bandits, road cutters, etc.), which is an ever present danger heightened by these desperate times. As for the Tãngpogse, the future is bleak, facilitating gold processing to continue would mean they could face the crisis while avoiding prostitution.

Alizèta Ouedraogo is a PhD student in Sociology and Anthropology at the University Lyon 2 (France) and team member of Gold Matters at IFSRA (Institute For Social Research in Africa), Burkina Faso. She works on artisanal gold mining in relation to gender and health in the South-West of Burkina Faso. Contact: lisaouedd@yahoo.fr

Gold Matters: Sustainability Transformations in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining: A Multi-Actor and Trans-Regional Perspective is a transdisciplinary research project which aims to consider whether and how a transformative approach towards sustainability can arise in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining (ASGM). For more information see www.gold-matters.org.

Cite as follows: A. Ouédraogo. (2020). Gold panning and the Covid-19 pandemic in southwestern Burkina Faso. www.gold-matters/org/?p=911