This blog is based on Chapter 12 of the book ‘Global Gold Production Touching Ground: Expansion, Informalisation, and Technological Innovation’, edited by Verbrugge and Geenen (2020).

Uganda: Gold – A National Treasure?

Eleanor Fisher, Lorenzo D’Angelo, Ronald Twongyirwe, and Esther van de Camp

The authors consider how elite privilege and entrenched inequalities undermine the potential for equity in the formalisation of mineral rights.

“Gold is a national treasure; it is not meant for only a few”

– President Yoweri Museveni, 2017

Gold deposits have stimulated prospecting interest in Uganda since the early twentieth century. Nevertheless, historically, there was no large-scale and only limited medium-scale gold mining, with gold extraction being the domain of artisanal miners. Large-scale mining and processing instead focused on blister copper and cobalt, feeding world demand from the mid-1950s, later to collapse in the face of escalating civil conflict.

After the current president and his ruling party – today called the National Resistance Movement (NRM) – came to power in 1986, little priority was given to developing the country’s mineral resources. However, in the early 2000s, revisions to minerals policy and legislation marked a move towards a more ‘investor-friendly’ national environment for mining. This was reinforced by the donor-funded Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources Project (SMMRP, 2004-2011), which sought to (re)invigorate the minerals sector, including through strengthening institutional capacity for artisanal and small-scale mining.

Harnessing the development potential of gold

Today government identifies mining as a priority sector within the ‘Uganda Vision 2040’. A revised Mining and Minerals Policy (2018) has been introduced and a new Mining and Minerals Act (2019) has been ratified. Placing emphasis on the development of an industrial mining sector, the formalisation of artisanal and small-scale mining is encouraged. Against this background, and in the context of a steady rise in the international price of gold, national elite and foreign interests have gravitated towards gold’s productive potential.

Alongside mining itself, the regional gold trade contributes to gold dynamics within Uganda. The trade is overwhelmingly informal and predominantly illegal, but with legitimate aspects entwining the formal and informal economies. In turn, the gold trade feeds into industrial gold refining, which has gained importance within government plans for revenue capture from gold. In 2017, the first industrial ‘African Gold Refinery’ started operations in Entebbe backed by Belgian gold magnate, Alain Goetz. Refined exports have led to a ‘gold boom’, with gold becoming the premier earner of foreign exchange in 2019. However, an estimated 90% of the refined ore is produced outside the country (EIU, 2019).

The United Nations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are critical of Uganda’s move into gold refining, claiming it includes illegally-traded gold from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), South Sudan, and Tanzania (The Sentry, 2018). Claims regarding the illicit regional gold trade have a long legacy in Uganda, having surfaced in the 1965–1966 ‘Gold Allegations Parliamentary Motion’ – which charged Idi Amin, then Deputy Commander of the Ugandan army, with looting gold from what is now the DRC. During the second Congolese war, between 1998 and 2003, Ugandan army figures were again implicated in gold extraction from DRC (Vlassenroot et al., 2012). Recent controversy over gold refining at African Gold Refinery also extends further afield, including in relation to the processing of gold produced in Venezuela.

President Museveni declares gold to be a ‘national treasure’ but dependence on refining using infrastructures backed by non-Ugandans and gold ore sourced externally, as well as extensive non-national interests in gold mining within Uganda, exposes trans-national contradictions in the politics of extraction. These contradictions bring to the fore the character of the political system and its relevance for understanding formalisation dynamics.

Uganda’s political system has been described as semi-authoritarian and neo-patrimonial, although Museveni has also been adept at exercising forms of ‘soft power’, through responsiveness to popular concerns and the management of political rivals (Golooba-Mutebe and Hickey, 2016). NRM leadership has delivered political stability and economic growth; however, its progressive character has diminished as the national elite struggle to stay in power. Museveni and his family exercise considerable influence on economic affairs and political loyalties are prized for the military. In this regard, national elite and army interests extend into gold mining, refining and trade both within Uganda and the wider region.

Formalising an Informal Sector

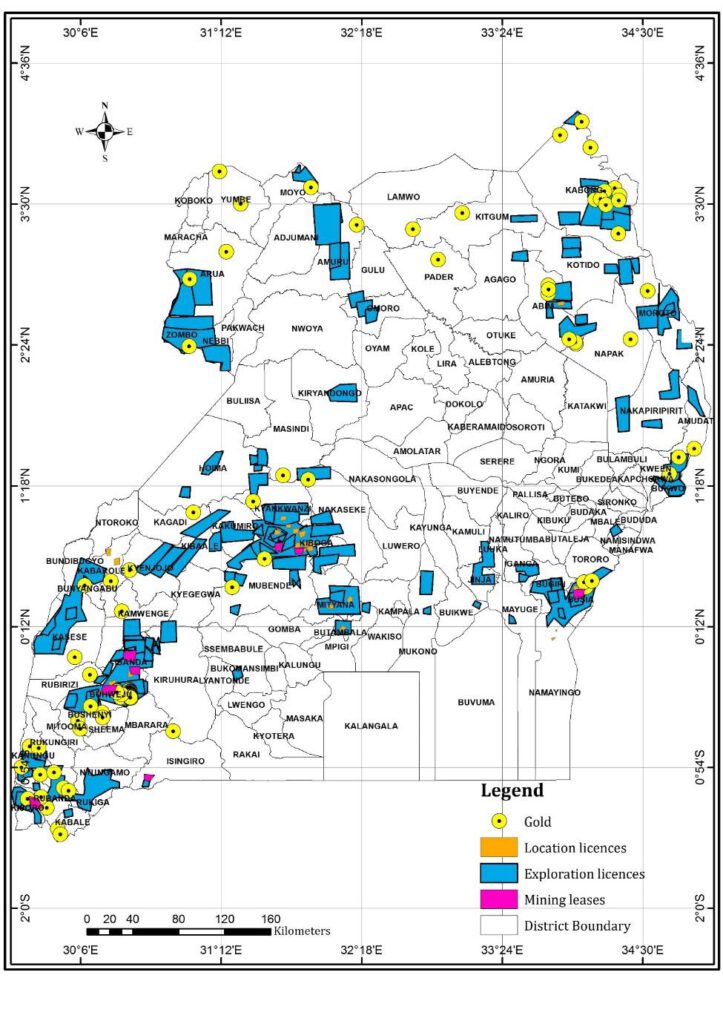

In the absence of large-scale transnational mining companies, the gold sector attracts smaller investors, both Ugandan nationals and foreign (e.g. from Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, India, Russia, Australia, UK, and China). Nevertheless, while many prospecting and exploration licences are issued, underinvestment in exploration has been a long-term challenge, as it has been in other parts of Africa (Luning, 2012). Alongside investors attracted to gold mining, there is a dynamic ASGM sector, including in the southwest (Kigezi, Buhweju), west (Kanungu), centre (Mubende), east (Busia, Namiringo), and northeast (Karamoja). ASGM gold extraction is primarily alluvial, although there is some manual hard rock mining.

Source: authors, drawing on http://portals.flexicadastre.com/uganda Accessed: 23.10.2019

Recent estimates on ASGM numbers include a figure of 40,000 miners (Barreto et al., 2018). ASM produces 90% of most minerals, including gold. In interview with one of the authors, the Acting Director of the Directorate of Geological Survey and Mines stressed the main problems facing ASGM development as being “disorganisation and lack of capacity building,” adding: “artisanal mining has two clusters, those artisanal miners who are disorganised and work like chickens in a garden scratching around, they find a fleck of gold and go to the bar … others are organised, they have an association with an address, the Commissioner can access them because they have an address, they do not have a license but they have an address. These are the miners we want to encourage.”

This distinction between ‘organised’ and ‘disorganised’ miners typifies how ASGM is approached by government. Until recently all artisanal mining was unlicensed and therefore inherently informal/illegal, thus being ‘disorganised’. Recent policy and legislation encourage ASGM formalisation, including through promotion of Artisanal and Small-scale Miner Organisations (ASMOs), facilitation of access to licences, credit and equipment, and provision of market information. In addition, the establishment of a police Mineral Protection Unit, is intended to ensure production is declared, although author interviews highlighted allegations of extortion.

To give examples of how the formalisation of ASGM has developed, in Mubende District, there was a rush for gold around 2012 attracting small-scale miners from Uganda and countries in the surrounding region. This gold rush stimulated interest by national and foreign investors seeking to acquire concessions to develop larger-scale operations. Move forward five years to 2017, following heightened conflict in which miners were accused of encroaching on the concessions of mining companies, soldiers and police evicted around 60,000 gold miners with their families. To highlight national elite connections, amongst company shareholders in conflict with ASGM was Gertrude Njuba, a presidential advisor and former ‘bush-war fighter’ in the liberation struggle.

Buss et al. (2017) suggest ASGM responded to the scramble for gold in Mubende by forming associations so they could obtain formalised mineral concessions. Fears over displacement also contributed to ASMO formation and concession applications in Busia (Fisher, 2018). ASMOs in Mubende and Busia have been supported by NGOs and it is amongst these groups that location licences (i.e. 16 hectares in size) are now concentrated. In the words of the Director of Environmental Women in Action for Development, working in Busia, “we made it easier for them, they started to register at the grassroots level, then the district, we helped them to leave Busia and go to the ministry and face officers, there was a lot of fear and misunderstanding”. New groups continue to form ASMOs, although if they do not have NGO support a ‘breakthrough’ to formalisation can be difficult. Additionally, studies point to elite capture and gender inequalities within ASMOs (Muheki and Geenen, 2018; Rutherford and Buss, 2019).

As demand for gold-rich land intensifies, action by government towards ASGM can be both punitive and supportive. Licence acquisition is encouraged but there is lack of wider institutional and financial support. Local government budgets for social, environmental and economic development of the sector are also substantially under resourced. Unsurprisingly, government favours those ASGM who form groups, with literate members who have capital, access to IT and bank accounts, and can complete licensing procedures, i.e. typically those who have NGO support and are amongst local elites. At the same time, a ‘disorganised’ majority — “scratching like chickens” — e.g. those working as mine labourers, processors, in service provision and petty trade in mining areas, remain overwhelmingly informal and unsupported either by government or NGOs.

Entrenched inequality undermining potential for equity

As we argue in a recent publication (Fisher et al., 2020), the politics of extraction in Uganda reveal how gold’s potential has become visible as a (trans)national treasure. A ruling party under pressure after over forty years in power frames this potentiality. The activities of mining companies have spawned heightened conflict with miners and mining communities, with the space – both physical and metaphorical – for informal ASGM contracting. In an all-too-familiar story regarding the process of formalising an informal sector, some groups of ASGM benefit more than others, gaining greater mineral right security and potential for capital accumulation. With increasing socio-technical differentiation coupled with underlying power and gender inequalities, benefits readily flow to elites – from village to national levels. This carries the danger that inequalities will be reinforced for a mining population already marginalised from development. Indeed, for gold to really become a ‘national’ treasure, equitable development needs to be promoted through investment in broad-based support for the ASGM sector.

Prof. Eleanor Fisher is Professor of International Development at the University of Reading, UK.

Dr Lorenzo D’Angelo is Senior Researcher in the Gold Matters project based at the University of Reading, UK.

Dr Ronald Twongyirwe is Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Environmental and Livelihoods Support Systems, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda.

Ms Esther van de Camp is doctoral candidate at the Leiden University undertaking a PhD on ASGM in Uganda with the Gold Matters project.

Gold Matters: Sustainability Transformations in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining: A Multi-Actor and Trans-Regional Perspective is a transdisciplinary research project which aims to consider whether and how a transformative approach towards sustainability can arise in Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining (ASGM). For more information see www.gold-matters.org.

Cite as follows: Fisher, E., D’Angelo, L., Twongyirwe, R. and Van de Camp, E. (2020) Uganda: Gold – A National Treasure www.gold-matters.org/?p=936